- For PC

- For MAC

- For Linux

- OS: Windows 10 (64 bit)

- Processor: Dual-Core 2.2 GHz

- Memory: 4GB

- Video Card: DirectX 11 level video card: AMD Radeon 77XX / NVIDIA GeForce GTX 660. The minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 23.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Windows 10/11 (64 bit)

- Processor: Intel Core i5 or Ryzen 5 3600 and better

- Memory: 16 GB and more

- Video Card: DirectX 11 level video card or higher and drivers: Nvidia GeForce 1060 and higher, Radeon RX 570 and higher

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 75.9 GB (Full client)

- OS: Mac OS Big Sur 11.0 or newer

- Processor: Core i5, minimum 2.2GHz (Intel Xeon is not supported)

- Memory: 6 GB

- Video Card: Intel Iris Pro 5200 (Mac), or analog from AMD/Nvidia for Mac. Minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p with Metal support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 22.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Mac OS Big Sur 11.0 or newer

- Processor: Core i7 (Intel Xeon is not supported)

- Memory: 8 GB

- Video Card: Radeon Vega II or higher with Metal support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 62.2 GB (Full client)

- OS: Most modern 64bit Linux distributions

- Processor: Dual-Core 2.4 GHz

- Memory: 4 GB

- Video Card: NVIDIA 660 with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) / similar AMD with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months; the minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p) with Vulkan support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 22.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Ubuntu 20.04 64bit

- Processor: Intel Core i7

- Memory: 16 GB

- Video Card: NVIDIA 1060 with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) / similar AMD (Radeon RX 570) with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) with Vulkan support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 62.2 GB (Full client)

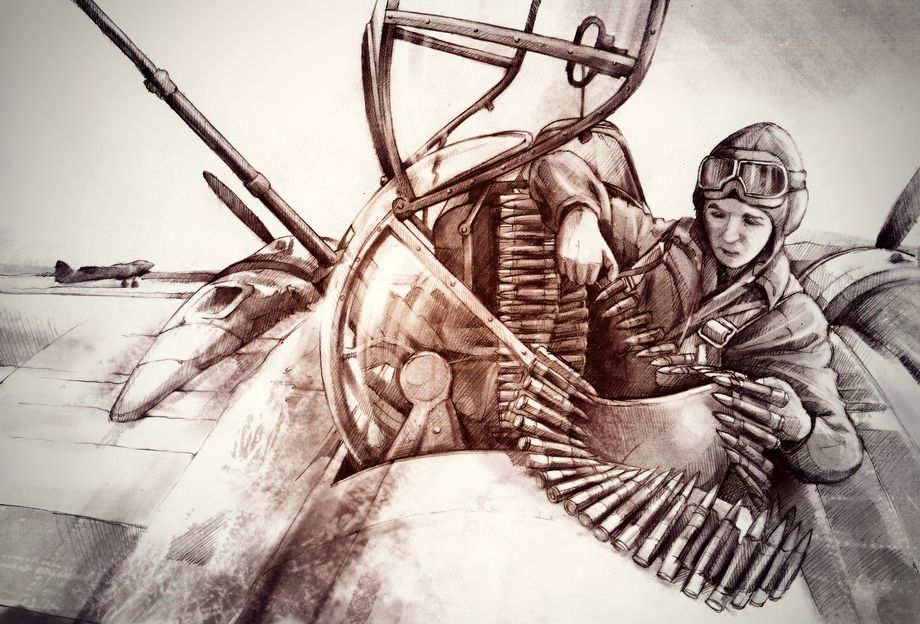

On May 12th 1940, five obsolete Fairey Battle light bombers of No.12 Squadron RAF took off from their base near Amifontaine in France. Under the command of Flying Officer Donald Garland, the five Battles attacked a strategically vital bridge over the Albert Canal in Belgium. Braving their way through intense anti-aircraft fire and decimated by German fighters immediately after releasing their bombs, the horrifically outperformed British aircraft were still able to deliver their bombs on target. Only one Battle returned to base. Of the crew of the lead aircraft, both Flying Officer Garland as pilot and Sergeant Thomas Gray as his observer were awarded their nation’s highest decoration for bravery – the Victoria Cross. But with them throughout, sharing the danger as he kept up a constant stream of fire from his single Vickers K machine gun, was 20 year old air gunner Leading Aircraftsman Lawrence Reynolds. He died with his crew. As he was deemed not to be in a position of leadership or influence, he was the only one of the three not to be awarded the Victoria Cross.

The vital role played by the air gunner has often been tragically left in the shadow of that of the pilot. Gunners required far less training and were therefore cheaper and easier to replace, and were not given powers of captaincy within the crew of an aircraft. Whilst there were many roles within multi-crew aircraft which also necessitated manning a machine gun, such as navigator, observer, radio operator or bombardier, it is the purpose of this article to examine only the air gunner: the brave individual whose sole job was to keep enemy fighters at bay.

It is easier to appreciate the gunner’s role within his crew by examining the crew itself: taking a typical USAAF bomber such as the B17, ten men were required to operate the aircraft. This consisted of two pilots, a navigator and a bombardier, all of whom were commissioned officers. A flight engineer and a radio operator flew alongside four dedicated gunners; these last six crew members were all non-commissioned. Aside from the two pilots, every crew member had at least one machine gun position immediately to hand in the event of attack by enemy aircraft.

|

|

For those conscripted into the armed forces in the Second World War, flying seemed like an attractive alternative to the infantry to many. With this in mind, applicants for officer aircrew roles within the USAAF were required to have completed a minimum of two years’ college education, although this was reduced to an entrance examination once casualties began to mount. Gunners were not expected to have as much of an academic background and therefore tended – although it certainly was not a rule – to come from less affluent backgrounds.

After basic training, those selected to become gunners would attend one of the USAAF gunnery schools. This consisted of six weeks of studying the operation and maintenance of both gun and turret, ballistics, enemy vehicle recognition and most importantly, live firing. Gunners trained to fire at land, sea and air targets as, although their primary role was no doubt the defense of their aircraft, there were also obvious offensive capabilities against land and sea targets inherent in their new role. For the USAAF, this same gunnery course formed part of the training for navigators, bombardiers, radio operators and flight engineers. At peak output, the USAAF was training 600 gunners every five weeks.

Comparisons can be drawn to the system employed in Germany for training gunners within the Luftwaffe. In the early days of the Second World War, new recruits were first assigned to a Flieger-Ersatzabteilung, or Aircrew Replacement Battalion, where after uniform issue and medical exams, the traditional core military skills of drill, physical training and weapons handling were also accompanied by basic navigation and radio operation. At the end of six months of training, recruits were streamed with those considered suitable being selected for pilot training. The remainder received a further two months training at an Aircrew Development Regiment, being instructed in further navigation and radio operation as well as technical training and gunnery. Later in the war, the streaming process was undertaken far earlier and potential gunners found themselves at the Aircrew Development Regiment almost immediately.

Those who were then selected to specialize as gunners, often accompanied by a number of individuals who had failed to make the grade during pilot training, were now sent to the Luftwaffe’s five month course on air gunnery. This involved familiarity with weapons ranging from handguns up to air-to-air machine gunnery in aircraft. The latter was initially wit gun cameras but then progressed onto towed targets with real ammunition. Airborne training was often conducted concurrently with other branches, with students and instructors of several specializations all crammed into a single training aircraft. Upon completion of training, gunners were sent to their front line squadrons.

Across many roles of every air force gunners suffered horrific casualties, notable in the statistics of RAF Bomber Command in Western Europe, through Soviet light bomber gunners on the Eastern Front to the gunners of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s carrier borne torpedo and dive bombers. Not afforded the rank or pay of their commissioned comrades, gunners took all of the same risks. This was recognised by some but all too often ignored by others, as highlighted in an anecdote told to the author by a Swordfish Telegraphist Air Gunner in the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm:

Whilst flying Anti-Submarine patrols from the icy deck of a tiny escort carrier within the Arctic Circle on a convoy run to the Soviet Union, a solitary Swordfish landed in the early hours of the morning. Whilst the aircraft was being prepared for its next patrol, the pilot of the three man crew decided it was a good time to finally sit down for a meal. Being in the early hours of the morning, most of the carrier’s facilities were shut down for the night.

“We’ll eat in the Wardroom,” the pilot decided.

The pilot and observer were both officers but the Telegraphist Air Gunner was a rating, and therefore not allowed in the officers-only Wardroom on a warship. The pilot refused to take no for an answer from his gunner. Whilst the three sat down for their meal, one of the ship’s officers stormed over and demanded that the pilot and observer remove their gunner from the Wardroom immediately.

The pilot calmly put down his cutlery and looked up at the naval officer.

“If we can die together, old boy,” he replied calmly, “we can dine together. Go away.”

Whilst the last two words he spoke have been altered by the author to make the quote suitable for a younger audience, the sentiment was the same and representative of those aircrew who were fiercely and rightly proud of their vital air gunners.

About The Author - Mark Barber, War Thunder Historical Consultant

Mark Barber is a pilot in the British Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm. His first book was published by Osprey Publishing in 2008; subsequently, he has written several more titles for Osprey and has also published articles for several magazines, including the UK's top selling aviation magazine 'FlyPast'. His main areas of interest are British Naval Aviation in the First and Second World Wars and RAF Fighter Command in the Second World War. He currently works with Gaijin Entertainment as a Historical Consultant, helping to run the Historical Section of the War Thunder forums and heading up the Ace of the Month series.