- For PC

- For MAC

- For Linux

- OS: Windows 10 (64 bit)

- Processor: Dual-Core 2.2 GHz

- Memory: 4GB

- Video Card: DirectX 11 level video card: AMD Radeon 77XX / NVIDIA GeForce GTX 660. The minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 23.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Windows 10/11 (64 bit)

- Processor: Intel Core i5 or Ryzen 5 3600 and better

- Memory: 16 GB and more

- Video Card: DirectX 11 level video card or higher and drivers: Nvidia GeForce 1060 and higher, Radeon RX 570 and higher

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 75.9 GB (Full client)

- OS: Mac OS Big Sur 11.0 or newer

- Processor: Core i5, minimum 2.2GHz (Intel Xeon is not supported)

- Memory: 6 GB

- Video Card: Intel Iris Pro 5200 (Mac), or analog from AMD/Nvidia for Mac. Minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p with Metal support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 22.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Mac OS Big Sur 11.0 or newer

- Processor: Core i7 (Intel Xeon is not supported)

- Memory: 8 GB

- Video Card: Radeon Vega II or higher with Metal support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 62.2 GB (Full client)

- OS: Most modern 64bit Linux distributions

- Processor: Dual-Core 2.4 GHz

- Memory: 4 GB

- Video Card: NVIDIA 660 with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) / similar AMD with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months; the minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p) with Vulkan support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 22.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Ubuntu 20.04 64bit

- Processor: Intel Core i7

- Memory: 16 GB

- Video Card: NVIDIA 1060 with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) / similar AMD (Radeon RX 570) with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) with Vulkan support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 62.2 GB (Full client)

From 14:00 GMT (6:00 PST) March 25th

to 14:00 GMT (6:00 PST) March 26th

30% discount for purchase and repair of dive bombers

Ju 87 R-2, Ju 87 B-2, Ju 87 D-3, Ju 87D-5, Ju 88 A-4, D3A1,

SBD-3 Dauntless, Ar-2, Pe-2-1, Pe-2-21, Pe-2-83, Pe-2-110, Pe-2-359

Dive bombing had been experimented with on offensive operations as early as the First World War. The concept was simple – the forward movement of any bombing platform would have a pronounced effect on any bombs dropped, resulting in a forward movement of the bomb rather than a simple vertical drop. This in turn led to problems with accuracy and the requirement for specialist bombsights to try to calculate a large number of variables involved. In theory, if an aircraft were to dive vertically down on top of a target, most of these variables would be eliminated, leading to far greater accuracy. However, the control response needed to actually pull out of the dive meant that particularly heavy aircraft were not able to attempt this maneuver. Furthermore, the stresses on the aircraft on pulling out of the dive were considerable enough to require strengthening of the airframe, resulting in the need for specialized design and manufacture to guarantee a good combination of safety and accuracy. Also, as heavier aircraft with large bomb loads were not suited to this role, the accuracy which came with dive bombing also brought the penalty of a smaller bomb load – hence, dive bombing was very much a precision attack against selected targets rather than a strategic attack. The faith placed in the accuracy of dive bombing was of note: Luftwaffe dive bomber pilots were expected to drop half of their bombs within 25 metres of the aim point. This meant that small, hard targets such as tanks were far more difficult to destroy than softer targets such as trucks, which would be eliminated by a near miss.

Dive bombing had been experimented with on offensive operations as early as the First World War. The concept was simple – the forward movement of any bombing platform would have a pronounced effect on any bombs dropped, resulting in a forward movement of the bomb rather than a simple vertical drop. This in turn led to problems with accuracy and the requirement for specialist bombsights to try to calculate a large number of variables involved. In theory, if an aircraft were to dive vertically down on top of a target, most of these variables would be eliminated, leading to far greater accuracy. However, the control response needed to actually pull out of the dive meant that particularly heavy aircraft were not able to attempt this maneuver. Furthermore, the stresses on the aircraft on pulling out of the dive were considerable enough to require strengthening of the airframe, resulting in the need for specialized design and manufacture to guarantee a good combination of safety and accuracy. Also, as heavier aircraft with large bomb loads were not suited to this role, the accuracy which came with dive bombing also brought the penalty of a smaller bomb load – hence, dive bombing was very much a precision attack against selected targets rather than a strategic attack. The faith placed in the accuracy of dive bombing was of note: Luftwaffe dive bomber pilots were expected to drop half of their bombs within 25 metres of the aim point. This meant that small, hard targets such as tanks were far more difficult to destroy than softer targets such as trucks, which would be eliminated by a near miss.

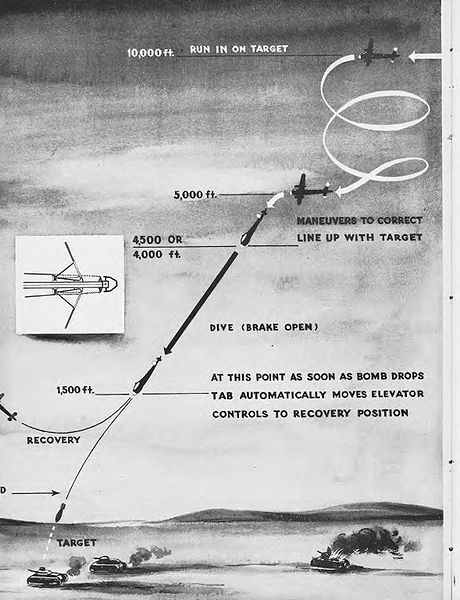

The standard attack as laid down for Luftwaffe dive bomber pilots flying the Junkers Ju87 was to commence the run in to the target from some 12,000 to 15,000 feet and at a speed of 160 mph. Cloud base and visibility made the initial height more variable in practice. However, an optimum height was sought after as too high would result in poorer visibility of smaller targets, and too low would lead to the target being spotted too late or an increased risk of receiving accurate defensive fire. The run was, ideally, carried out into wind as crosswind could have significant effects on the accuracy of bombing once the bombs were dropped.

In the case of the Ju87, the pilot was aided by a clear view panel in the floor of the cockpit; when the target was in position the pilot would pull a lever which would extend the dive brakes and trim the aircraft to a nose down position for the dive; this would be some 70 to 80 degrees pitch down below the horizon. Even with the dive brakes deployed the aircraft’s speed increased markedly in the dive, peaking at some 350 mph. During the dive the pilot was in a position to make minor corrections to the aircraft’s fight path to keep his sights on target; meanwhile, the radio operator/gunner was in the rather unenviable position of diving backwards towards the ground at over 300 mph, looking straight up at the sky! The next event in the attack run would be an audio warner sounding in the cockpit at a preset height – normally in the region of 4300 feet – to alert the pilot that he was approaching the height for dropping bombs. The audio klaxon would then silence after around 2000 feet and the pilot would drop the bombs: the very action of dropping bombs would trigger the Ju87’s automatic dive recovery, during which both crewmembers were subjected to significant G-forces. It was at this stage that the dive bomber was perhaps at its most vulnerable; speed decreasing, climbing automatically and with G-forces partially incapacitating the crew.

The profile was similar in many ways for other aircraft types, although heavier designs such as the Junkers Ju88 employed a shallower dive, typically between 50 and 60 degrees.

For the US Navy, dive bombing was of equal importance but tactically for different reasons: dive bombing was perhaps the most accurate way of hitting a relatively small, moving target such as a warship and also the logistical implications of operating from an aircraft carrier precluded the use of larger, multi-engine bombers. The US Navy used two terms to describe their two standard attacks from this weapon platform: the ‘Glide’ attack and the ‘Dive-Bomb’ attack.

From the US Navy’s point of view, a Glide Attack was any attack commenced from less than 8000 feet or less than 70 degrees pitch down below the horizon. US Naval Doctrine stated that 70 degrees angle of dive was optimal not only for accuracy, but also minimizing danger from enemy fire. US Navy dive bombers would approach their target from a similar altitude to their Luftwaffe counterparts, normally some 15,000 feet if not higher. The attacking formation would close to the Initial Point – 10 miles from the target – before then splitting into smaller groups so as to be able to attack the target from several angles simultaneously, which would in theory saturate the enemy defences. For a Dive-Bomb attack, the run itself would commence from the run in altitude of 15,000 to 17,000 feet, at the optimum angle of 70 degrees with the dive brakes extended. The dive was continued down to 2500 feet at which point the bombs were released and the aircraft would commence a level off, aiming to exit the target area at a little over wave top height whilst carrying out small deviations in course and altitude so as to throw off enemy gunners.

For British Naval pilots of the Fleet Air Arm, there were further variations still. Fleet Air Arm tactics and techniques were similar to those of the US Navy in that a height of some 15,000 feet was common for the run in, although again in practice the poor weather of some theatres often reduced this to as low as 6000 feet. The angle of dive was 65 degrees – something of a middle ground between the steep dives of American and German bombers and the more shallow dive of Japanese doctrine – with the pilot aiming to release bombs at between 1500 and 2000 feet. Fleet Air Arm doctrine also stated that in the event of carrying out an attack on shipping, the attack was to be carried out from astern so as to reduce the complication of a closing target. After releasing bombs, the dive bomber would either pull sharply away or level off at wave top height, depending on what the main threat was perceived to be.

Fuselage Art of Ju-87B, flown by Lt. Hubert Polz, 6/StG2, Libya 1942 - decal will be added in on of the future updates.

Artist - Fenris.

The author

Mark Barber, War Thunder Historical Consultant

Mark Barber, War Thunder Historical Consultant

Mark Barber is a pilot in the British Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm. His first book was published by Osprey Publishing in 2008; subsequently, he has written several more titles for Osprey and has also published articles for several magazines, including the UK's top selling aviation magazine 'FlyPast'. His main areas of interest are British Naval Aviation in the First and Second World Wars and RAF Fighter Command in the Second World War. He currently works with Gaijin Entertainment as a Historical Consultant, helping to run the Historical Section of the War Thunder forums and heading up the Ace of the Month series.