- For PC

- For MAC

- For Linux

- OS: Windows 10 (64 bit)

- Processor: Dual-Core 2.2 GHz

- Memory: 4GB

- Video Card: DirectX 11 level video card: AMD Radeon 77XX / NVIDIA GeForce GTX 660. The minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 23.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Windows 10/11 (64 bit)

- Processor: Intel Core i5 or Ryzen 5 3600 and better

- Memory: 16 GB and more

- Video Card: DirectX 11 level video card or higher and drivers: Nvidia GeForce 1060 and higher, Radeon RX 570 and higher

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 75.9 GB (Full client)

- OS: Mac OS Big Sur 11.0 or newer

- Processor: Core i5, minimum 2.2GHz (Intel Xeon is not supported)

- Memory: 6 GB

- Video Card: Intel Iris Pro 5200 (Mac), or analog from AMD/Nvidia for Mac. Minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p with Metal support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 22.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Mac OS Big Sur 11.0 or newer

- Processor: Core i7 (Intel Xeon is not supported)

- Memory: 8 GB

- Video Card: Radeon Vega II or higher with Metal support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 62.2 GB (Full client)

- OS: Most modern 64bit Linux distributions

- Processor: Dual-Core 2.4 GHz

- Memory: 4 GB

- Video Card: NVIDIA 660 with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) / similar AMD with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months; the minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p) with Vulkan support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 22.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Ubuntu 20.04 64bit

- Processor: Intel Core i7

- Memory: 16 GB

- Video Card: NVIDIA 1060 with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) / similar AMD (Radeon RX 570) with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) with Vulkan support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 62.2 GB (Full client)

A combat aircraft’s armament is just as important in determining its fighting ability as the pilot and aircraft itself. The right combination of weapons under the right circumstances is a determining factor which can elevate even the most average of aircraft into a deadly warplane. To explore this, it must be asked: how did armaments evolve?

|

The first air armaments were Rifle Caliber Machine-guns (RCM), with sizes varying roughly from 6mm to 9mm, and the Heavy Machine-Gun (HMG, reference to diameter not weight) ranging 10mm to 15mm (including the .50 inch caliber).

When the First World War broke out in mid 1914, the concept of aerial combat was seen more as a fiction than reality so there was limited thought into the design of specific air armaments. Still, some did foresee the possibility battles in the air would develop, and machine-guns were an obvious choice over pistols and rifles. Most early airborne machine-guns where either based on the Maxim (machine) Gun, Danish Madsen, or the new Lewis machine-gun, however neither were optimal; a similar reality for the first aircraft pressed into combat.

As the war progressed, increased aircraft load capacity and better performing machine guns resulted in the production of the iconic twin machine-gun bi-plane fighter. Of course other armaments did exist but it was almost entirely RCM armaments and simple solid shot rounds, often called “Ball” (holdover term from musket ball) that found their way onto aircraft. During the war, John Moses Browning introduced the highly reliable M1917 machine-gun to the US Army that later lead to the development of the improved M1919 M1 .30-06 Springfield (7.62x63) specialized aircraft version. This was later re-chambered as the British .303 (7.62x56mmR) and found its way on virtually all British warplanes post WWI and well into WW2.

.jpg) |

On the European front in 1918, US General Pershing witnessed early armoured defenses, armoured vehicles, and even the world's first armoured aircraft: the Junkers J.I. Following this, he demanded something that would be capable of combatting them. Working almost simultaneously on the M1919, Browning created what would eventually be the M1921 M2 .50 inch BMG (B for Browning,12.7x99mm), effectively a scaled up M1919 and .30-06 cartridge; however, he would not stop its design there. Browning and company continued to tinker with the design, improving it further into arguably the best HMG in the world. It was not until years later that other companies and nations would devote the amount of time and effort to further produce and improve their own armament variants.

Conversely, aviation technology accelerated as material science and cheaper production offered an abundance of stronger materials with improved structural designs, which in turn allowed aircraft builders to replace vulnerable wood and fabric with largely superior metal structures. Higher speeds and larger payloads where possible, and ambitious goals in civilian aircraft were often met to much fanfare, at times producing better results than expected. This “golden age” of aviation, as it is called, was a tremendous technological revolution.

Curiously, as aircraft performance rapidly improved year after year, aircraft armaments generally remained the same: just 2 RCM machine-guns, and some with 4. There were, however, other configurations that were proposed and used - including HMG’s and the first fighter mounted cannons in the mid 1930’s - RCM’s, however, remained the norm. Reliance on RCM reached a crescendo in November 1934 when RAF Squadron Leader Ralph Sorley specified all future RAF fighters should be armed with no less than eight RCM’s, arguing that engagement times in combat would be fleeting at best, and more rounds in the air were needed. What he, and most others, failed to realize was that more modern use of materials made aircraft resistant to RCM armaments.

|

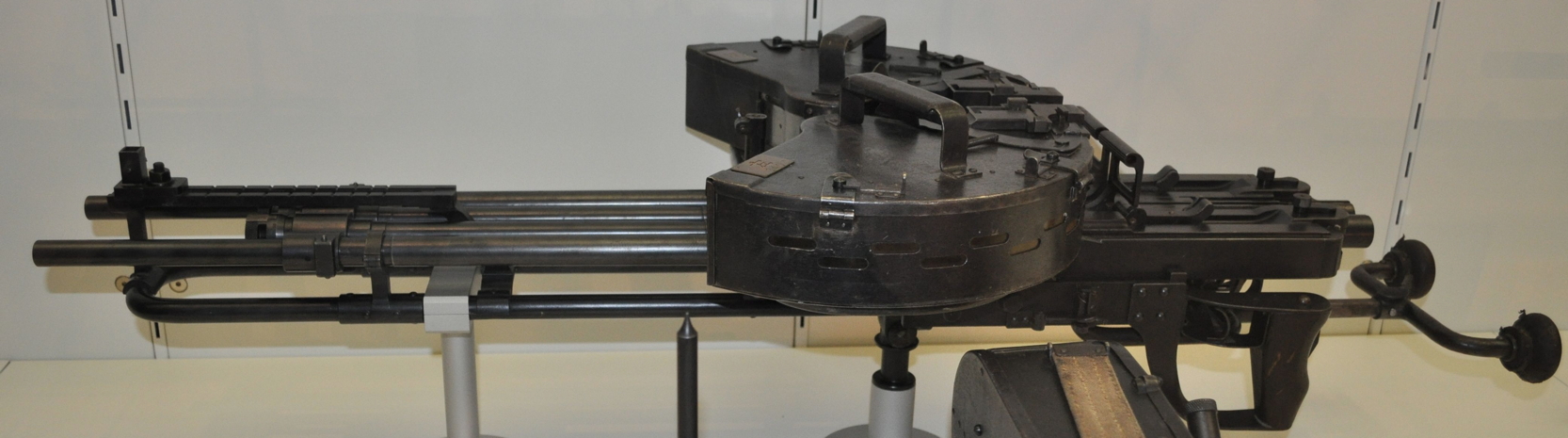

During the Battle of Britain, many Luftwaffe bombers were able to return to French shores. Although they would be riddled with bullet marks and holes, and keeping in mind that many would never fly again, it seemed to the RAF that they were shooting paper wads. Equipping Hurricane Mk. IIB fighters with 12 RCM’s did not seem to improve the situation. The Luftwaffe also discovered the same reality, and determined that even 20mm cannon rounds had difficulty against larger aircraft. However efforts to create better RCM configurations continued, Germany combined two MG-81J armaments together into the intimidating MG-81Z, and the Russians developed certainly the ultimate machine-gun ever produced: the Ultra-ShKAS (Ultra-ШКАС) which was capable of firing an astounding 3000 rounds per minute (but was still soon abandoned for cannon). Despite RCM’s minimal impact, it was seen that cannons also had many shortcomings, and even the 13mm sized HMG’s could not easily fit into the space allocated initially designed for RCM. As a result, RCM armaments persisted in many aircraft, being used well past their combat effectiveness. This was a most notable feature in Luftwaffe aircraft.

Across the Atlantic, the USAAF made use of the Browning lightened aircraft version of its M1921 .50 inch 12.7x99mm HMG. The long, but steady development, resulted in the AN/M2 variant and its inclusion in some fighter aircraft in the late 30’s. With the experiences in Europe, it did not take long to ramp up production and make it standard in the US air force’s warplanes, happening much sooner than other factions, which were just finishing their HMG designs. It was also later that the RAF adopted the AN/M2 instead of the Vickers HMG. Also based on it was the slightly inferior Italian Breda-SAFAT and heavily modified unique Japanese Ho-103/104. The semi-original Russian Berezin was on par, but somewhat better, than the AN/M2. Arguably, the champion proved to be the German MG-131, which was astoundingly 56% lighter and smaller whilst maintaining firepower close to that of the Browning AN/M2. This proved a key advantage for fighter aircraft, but eventually, it was only used in small amounts by the Luftwaffe mostly latter Bf-109 and FW-190 models.

While many sides had to deal with various combat mission profiles and targets, the Americans found themselves in a very advantageous situation, where the vast majority of enemy aircraft they faced were more vulnerable fighter; the Browning M1921 AN/M2 HMG was an ideal weapon in fighter engagements. It also proved devastating against land and sea units due to its fire rate, velocity, mass, and penetrating qualities, aided with multiple installations. It also made the logistics significantly simpler, including training and maintenance (coupled with its near identical M1919 .303), making it standard in nearly every US aircraft . At the time, it was the perfect weapon for the US military and USAAF in particular, making it a legend of the time, and a major weapon in many countries to this day.

Author: Joe “Pony51” Kudrna