- For PC

- For MAC

- For Linux

- OS: Windows 10 (64 bit)

- Processor: Dual-Core 2.2 GHz

- Memory: 4GB

- Video Card: DirectX 11 level video card: AMD Radeon 77XX / NVIDIA GeForce GTX 660. The minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 23.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Windows 10/11 (64 bit)

- Processor: Intel Core i5 or Ryzen 5 3600 and better

- Memory: 16 GB and more

- Video Card: DirectX 11 level video card or higher and drivers: Nvidia GeForce 1060 and higher, Radeon RX 570 and higher

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 75.9 GB (Full client)

- OS: Mac OS Big Sur 11.0 or newer

- Processor: Core i5, minimum 2.2GHz (Intel Xeon is not supported)

- Memory: 6 GB

- Video Card: Intel Iris Pro 5200 (Mac), or analog from AMD/Nvidia for Mac. Minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p with Metal support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 22.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Mac OS Big Sur 11.0 or newer

- Processor: Core i7 (Intel Xeon is not supported)

- Memory: 8 GB

- Video Card: Radeon Vega II or higher with Metal support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 62.2 GB (Full client)

- OS: Most modern 64bit Linux distributions

- Processor: Dual-Core 2.4 GHz

- Memory: 4 GB

- Video Card: NVIDIA 660 with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) / similar AMD with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months; the minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p) with Vulkan support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 22.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Ubuntu 20.04 64bit

- Processor: Intel Core i7

- Memory: 16 GB

- Video Card: NVIDIA 1060 with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) / similar AMD (Radeon RX 570) with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) with Vulkan support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 62.2 GB (Full client)

Typhoon Mk.Ia from no.56 squadron RAF camouflage created by DarkSoul79 | Download Here

The Ugly Duckling series has looked at a number of aircraft which are perhaps less popular than others in War Thunder, but has then gone on to detail how in real life these aircraft were actually very capable within their field. This month, we’re taking a different approach – an aircraft which is relatively popular within the game, but in real life fell far short of the mark…

|

Within the confines of military aviation history, the Hawker Typhoon is far from an obscure aircraft; in fact, it is something of a household name. Famous for its untiring support of allied forces during the Normandy campaign, rocket firing Typhoons employed by the 2nd Tactical Air Force were a symbol of dread to many a German soldier. However, perhaps less well known are the less than stellar origins of the Typhoon. In fact, it would perhaps be fair to say that it began its service life as nothing short of an unmitigated disaster.

The Hawker team began work on the Typhoon in 1937, knowing full well that the then new Hurricane would still need a replacement at some point. The prediction proved to be accurate – in January 1938 the British Air Ministry issued specification F.18/37, calling for a replacement for the Hurricane and Spitfire which should be armed with twelve machine guns and have a top speed in excess of 400 mph. The two engines available were the Rolls-Royce Vulture and the Napier Sabre, both predicted to deliver some 2000 hp; Hawker developed two prototype lines to coincide with the two engines. The Hawker Tornado would be powered by the Vulture whilst the Hawker Typhoon would be fitted with the Sabre.

Both engines suffered significant problems during the development phase and Rolls-Royce, already snowed under with both the production and the development of the Merlin, opted to abandon the Vulture, despite orders for 500 Tornadoes having already been placed following the successful first flight of the prototype. This left Napier with the Sabre powered Typhoon project, which first took to the skies on February 24th, 1940. Testing continued until May 1940, when the prototype suffered from major structural failure in the fuselage whilst in flight. A second prototype was also developed, armed with four 20mm Hispano cannons and first flying in May 1941.

|

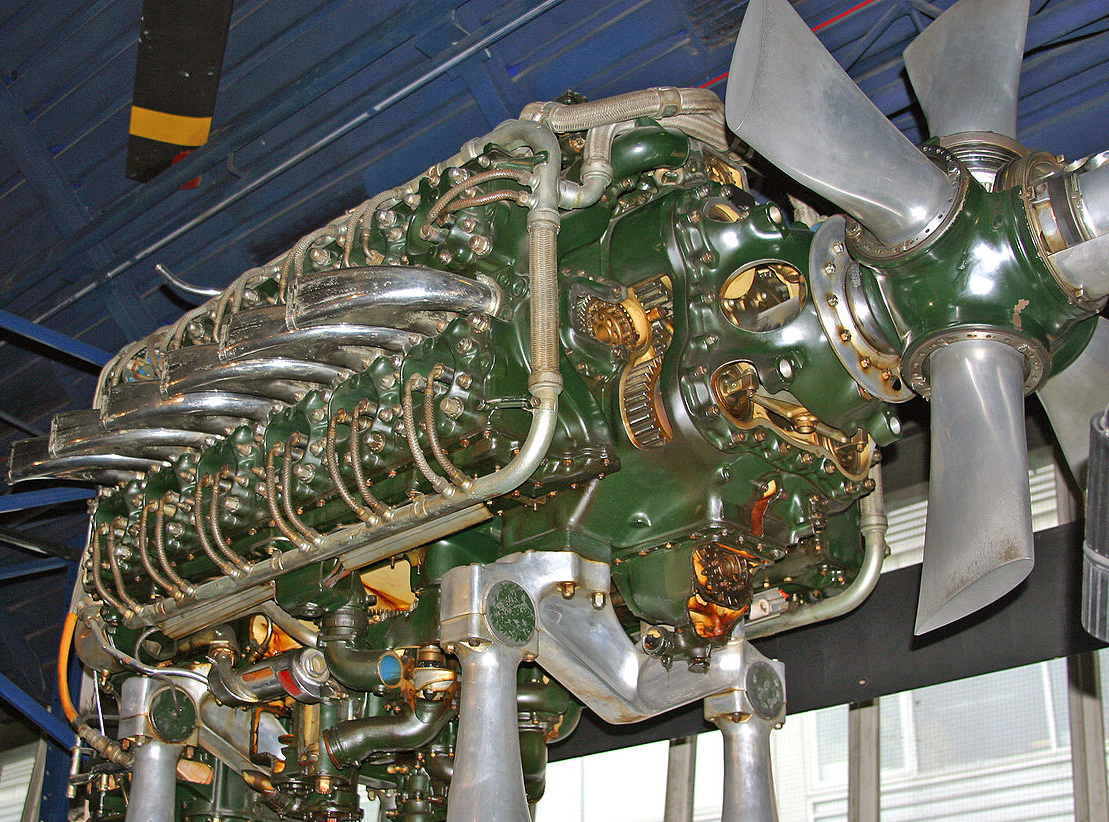

| Napier Sabre engine |

May 1941 also saw the first flight of a production Typhoon intended for front line service. Some 110 Typhoons would be fitted with twelve 0.303 inch machine guns and designated Mk.Ia; the remainder of the production run over the course of the next few years resulted in over 3200 Mk.Ibs armed with four 20mm cannons. No.56 Squadron based at RAF Duxford were the first to receive the Typhoon in September 1941, and here the real problems began.

The accident rate of the new fighter was increasing, noticeably. Not only were fatalities occurring on front line squadrons, but also with pilots who were test flying aircraft ready for delivery. Isolating the problem with the unpopular new fighter was made far more difficult by the fact that it was not one isolated issue. Aside from the huge factor of numerous fatal accidents with as of yet unknown causes and continuing reliability problems with the Sabre powerplant, the Typhoon’s performance actually left a lot to be desired anyway. Intended as a fighter and interceptor, the Typhoon’s maneuverability left a lot to be desired, particularly at medium to high altitude, and its rate of climb was far from that originally promised. Voices echoing around the Air Ministry even began to call for the Typhoon to be removed from service and discontinued before it was too late.

Nonetheless, Hawker vowed to get to the bottom of these numerous problems:

-Engine reliability. This was eventually tied down to deformed sleeve valves which often caused the engine to seize and fail. However, this was not remedied until mid 1943.

-Fatal accidents. In November 1941 a Typhoon, seemingly completely intact, crashed into the ground with no response from the pilot. There is anecdotal evidence to support the claim that this was not an isolated incident. The problem in this case was found to be carbon monoxide poisoning from the engine due to insufficient sealing around the cockpit. Whilst sealing was improved the problem was never eradicated, and the Typhoon suffered the ignominy of being the only aircraft in the RAF’s history where the pilot was forced to be on oxygen from before starting his engine to after shutting down on completion of flying.

-Even more fatal accidents. A worryingly increasing trend was being reported back from Typhoon pilots – the entire tail was detaching in flight. Those lucky enough were able to escape via parachute, but some reports came back from pilots who watched their comrades plummet to their deaths with a tail-less fighter. Hawker identified that the rear fuselage joint was not strong enough and also particularly susceptible to fatigue, and the joint was strengthened. However, later investigations pinned the cause to elevator flutter and the only real solution to the issue was a different tail, as fitted to the Typhoon’s replacement – the Tempest.

-Further problems. Engines continued to fail. The Typhoon had issues with aileron reversal; the problem where, in some flight configurations, pilot control input will result in the exact opposite of what was demanded. High speed buffeting and instability was also a regular complaint, which was far from ideal in an aircraft which boasted top speed as one of its few real qualities.

|

Bit by bit, the Typhoon’s problems were reduced to finally leave the RAF with a useable aircraft. However, even after the reliability issues had been addressed nothing could be done for the Typhoon’s performance and it was relegated to duties as low level, such as interception and ground attack. With an inline engine whose coolant system could be taken out with a single bullet, the Typhoon was far from being ideal for ground attack and more found itself in this role as it was unable to carry out its intended job, rather than by design.

By the time the Typhoon was achieving notoriety over Normandy and causing havoc at the Falaise Gap, it was a very different aircraft to the disastrous twelve gun Mk.Ia which first attempted to replace the Spitfire and Hurricane as a true fighter. The later Mk.Ib Typhoons were loved and praised by many of their pilots, but it would take the development of the Tempest to finally eliminate the problems once and for all.

About The Author

|

Mark Barber, War Thunder Historical Consultant Mark Barber is a pilot in the British Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm. His first book was published by Osprey Publishing in 2008; subsequently, he has written several more titles for Osprey and has also published articles for several magazines, including the UK's top selling aviation magazine 'FlyPast'. His main areas of interest are British Naval Aviation in the First and Second World Wars and RAF Fighter Command in the Second World War. He currently works with Gaijin Entertainment as a Historical Consultant, helping to run the Historical Section of the War Thunder forums and heading up the Ace of the Month series. |