- For PC

- For MAC

- For Linux

- OS: Windows 7 SP1/8/10 (64 bit)

- Processor: Dual-Core 2.2 GHz

- Memory: 4GB

- Video Card: DirectX 10.1 level video card: AMD Radeon 77XX / NVIDIA GeForce GTX 660. The minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 17 GB

- OS: Windows 10/11 (64 bit)

- Processor: Intel Core i5 or Ryzen 5 3600 and better

- Memory: 16 GB and more

- Video Card: DirectX 11 level video card or higher and drivers: Nvidia GeForce 1060 and higher, Radeon RX 570 and higher

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 95 GB

- OS: Mac OS Big Sur 11.0 or newer

- Processor: Core i5, minimum 2.2GHz (Intel Xeon is not supported)

- Memory: 6 GB

- Video Card: Intel Iris Pro 5200 (Mac), or analog from AMD/Nvidia for Mac. Minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p with Metal support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 17 GB

- OS: Mac OS Big Sur 11.0 or newer

- Processor: Core i7 (Intel Xeon is not supported)

- Memory: 8 GB

- Video Card: Radeon Vega II or higher with Metal support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 95 GB

- OS: Most modern 64bit Linux distributions

- Processor: Dual-Core 2.4 GHz

- Memory: 4 GB

- Video Card: NVIDIA 660 with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) / similar AMD with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months; the minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p) with Vulkan support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 17 GB

- OS: Ubuntu 20.04 64bit

- Processor: Intel Core i7

- Memory: 16 GB

- Video Card: NVIDIA 1060 with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) / similar AMD (Radeon RX 570) with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) with Vulkan support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 95 GB

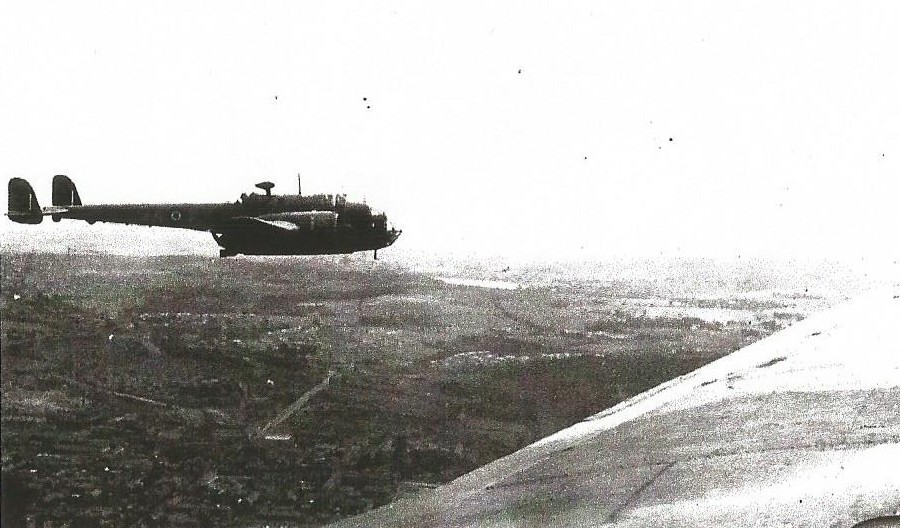

An exclusive interview with a RAF Coastal Command pilot Flight Lieutenant Brian Beattie obtained by our permanent author Mark Barber for the War Thunder official website. Read Part One here!

Whilst defensive fire from shipping was the most common form of enemy action, the threat from the air still existed.

Whilst defensive fire from shipping was the most common form of enemy action, the threat from the air still existed.

“Another time, half way across the North Sea on the way out for a Rover, way out to starboard we saw a shape – one of the AGs (Air Gunner) said ‘It’s alright, it’s a Beaufighter.’ I wasn’t expecting that as we hadn’t been told about any friendly squadrons operating in the area, but we carried on Eastward. The other aircraft was converging, and got much closer. The same AG then said ‘Sorry Skipper, it looks like a Ju88.’ I said ‘Thanks very much,’ or words to that effect, so we turned away. He was faster and getting uncomfortably close. I jettisoned the torpedo – 2000 pounds in weight, 2000 pounds in cost, apparently – but he was still faster. He came right round in front of us as we were heading West for home and flew ahead of us rather than firing with the guns in his nose. His rear gunner opened up on us, but did not hit. All I can guess is that he had already used up all the ammunition on his front guns. Our W/O (Wireless Operator) sent back a message that we had an encounter with an e/a (Enemy Aircraft), and that we were returning to base undamaged. When we got back and landed we were chased down runway by a fire engine and an ambulance. Apparently some idiot had decoded our message as us being damaged.”

After completing his tour with 489 Squadron, Beattie was rotated out of a front line post as was typical for British aircrew throughout the Second World War. He spent the next twelve months as an instructor, mainly on Beauforts.

“I spent the first 6 months of my instructional tour at RAF Turnberry in Scotland, teaching torpedo delivery. I then went on to No.9 OTU. Coming towards the end of my twelve month rest, some bright spark posted me to Lulsgate Bottom to the flying instructors course, having spent the last eleven months already being employed as a flying instructor. I did the 3 week course in July 1944, flying Oxfords. I was now a QFI (Qualified Flying Instructor) and very proud of that. So, having instructed for 11 months and then taken the course to qualify as an instructor, I was then told that I was going back on ops. I was sent to Dyce to learn how to fly Mosquitoes. Next, I was posted to No.248 Squadron at RAF Portreath in Cornwall.” No.248 Squadron had the normal A Flight and B Flight, both equipped with the Mosquito Mk.VI, but also had an ‘SD’ Flight equipped with the Mosquito Mk.XVIII, the ‘Tsetse’.

Beattie initially had the wrong impression regarding his new role. “I thought SD was Special Duties, which made me feel very important. I later found out it was Special Detachment and we weren’t technically part of the squadron. Our new Mosquito variant was called the Tsetse because its bite was a little bit nastier than the bite of a normal Mosquito. We had the Molins gun, 24 rounds and extra armour. The shell itself was about 6 ¾ pounds in weight and it had an Armour Piercing nose. There was a little hole at back end for the tracer; we could see a little red flame. The gun started life as a 57mm anti-tank gun, but took on the name Molins with us. The problem during development was how to make it automatic and get rid of empty shell cases as the nose of the Mosquito was far too small to have a crewmember working in it. Molins were the company who developed the mechanism; before the war, Molins had manufactured cigarette machines. It sounds weird, but it made sense as they had worked on automatic mechanisms in their cigarette machines. They took this design and made it bigger, so there was a sort of a little railway at the back of the gun, arranging rounds in clips. We could fire single shots, or fire one round every 2 seconds on automatic.”

Beattie describes the Mosquito’s legendary handling characteristics. “It was an incredible aircraft to fly, although I didn’t spend as long on it as the Hampden, which I was more used to. So, in a way, I didn’t have long enough to truly fall in love with it as a lot of other pilots seemed to.”

By this point in the war, Allied air superiority had increased significantly and so in September 1944, No.248 Squadron and their SD Flight were posted up to Banff in Scotland, near Inverness. It was ideally placed to house Coastal Command strike aircraft for attacks against enemy shipping in the North Sea. As a rather unique weapons platform, new tactics had to be developed for the Tsetse Mosquito.

“We aimed at waterline – we fired in a dive so as to make a second exit wound lower down and below the waterline. If it hit something inside it would shatter and cause debris damage. For my first demonstration of the gun we went up to practice with 11 rounds. We used to fly out into the Moray Firth, drop a smoke float then climb up to 3000 feet before peeling off and leveling at 2500 feet to then shoot at the smoke float in dive. No deflection necessary. We were told it had the highest muzzle velocity of any gun in the service, brought about by the fact the aircraft was already diving at some 300 knots.”

“We aimed at waterline – we fired in a dive so as to make a second exit wound lower down and below the waterline. If it hit something inside it would shatter and cause debris damage. For my first demonstration of the gun we went up to practice with 11 rounds. We used to fly out into the Moray Firth, drop a smoke float then climb up to 3000 feet before peeling off and leveling at 2500 feet to then shoot at the smoke float in dive. No deflection necessary. We were told it had the highest muzzle velocity of any gun in the service, brought about by the fact the aircraft was already diving at some 300 knots.”

After nine hours on Mosquitoes, Beattie’s first Op was on October 1st 1944; a relatively uneventful patrol lasting 3 hours 40 minutes. A second op was cancelled a few days later due to a smell of burning in the aircraft whilst on transit to the patrol area. The first time Beattie saw action with the Tsetse was in Hjelte fjord, where he attacked a barge and a second vessel. After firing 14 rounds he registered 4 hits. A second op over the same fjord followed shortly, where he recorded one hit on a merchant vessel. “If we missed we saw a splash in the water. If there was no splash then you’d hit the target. You didn’t wait to see if you got a hit, you kept firing.” Despite what some internet sources say, the four .303 guns were not used for aiming. “We actually often only had two .303s and I never fired them once. There wouldn’t have been time to use them for aiming, the attack run happened so fast. We’d go in last – the Mk.VI with the 20mm would go in first, then rocket Mosquitoes, then us. We’d arrive last and shout ‘salvo’ over the radio – the codeword to announce our attack run with the Molins gun - and everybody else would scatter.”

One particular sortie in the Tsetse Mosquito stands out for Beattie, perhaps more so than any other. In early December the Mosquitos were tasked to carry out a strike with the Beaufighter Wing stationed at Dallachy consisted of No.144 Squadron of the RAF, No.404 Canadian squadron, No.455 Australian and Beattie’s former squadron, No.489 New Zealand. Along with No.315 (Polish) Squadron’s Mustangs from RAF Peterhead, the formation crossing the North Sea now consisted of the three Mosquito squadrons from Banff; No.248 with their SD Flight, No.235, and No.143 squadrons, as well as the Beaufighter Wing and the Polish Mustangs. This was the first and only operation where Beaufighters and Mosquitoes worked in this role together, as the Beaufighter’s cruising speed was a lot slower.

One particular sortie in the Tsetse Mosquito stands out for Beattie, perhaps more so than any other. In early December the Mosquitos were tasked to carry out a strike with the Beaufighter Wing stationed at Dallachy consisted of No.144 Squadron of the RAF, No.404 Canadian squadron, No.455 Australian and Beattie’s former squadron, No.489 New Zealand. Along with No.315 (Polish) Squadron’s Mustangs from RAF Peterhead, the formation crossing the North Sea now consisted of the three Mosquito squadrons from Banff; No.248 with their SD Flight, No.235, and No.143 squadrons, as well as the Beaufighter Wing and the Polish Mustangs. This was the first and only operation where Beaufighters and Mosquitoes worked in this role together, as the Beaufighter’s cruising speed was a lot slower.

“On Norwegian capers,” Beattie continues, “the leader would go on ahead and recce where we were going and then control which ships were attacked. This was one of our longest operations. One of No.248 Squadron’s Flight Commanders was leading whole thing, the rest of formation carried on with the deputy leader leading us. We made landfall at Stattlandet perfectly on target. Under the deputy, we carried on up to the North East for some 30 miles. This was a lot further than we had been briefed; I had a good idea that something was going wrong with the navigation in the deputy formation leader’s aircraft, and I’d imagine quite a few more of the formation were thinking the same thing. However, radio discipline did not allow any communication; we were well disciplined so I shut up and followed my leader. A few minutes later I glanced down and saw single engine fighters taking off to meet us.”

The formation had strayed over Gossen airfield and now the Bf109s and FW190s of Luftwaffe veteran fighter wing JG5 scrambled to meet them.

“We all mixed up. The four Tsetses were at back end. We were heavier and less maneuverable and also had extra armour plating. When the fun started, we were at about 3000 feet. I glanced up to starboard and saw one of our Tsetses disintegrate after being hit by a single engine fighter. A second Tsetse, an ex pupil of mine, was also shot down but I didn’t see what happened. I was aware of some red stuff coming past us, so I started doing some violent evasive action. I thought afterwards that it was after some incredibly clever evasive action, at the bottom end of the dive at sea level, that my piloting had shaken off the German fighter. Lofty, my navigator, had looked back and as we had exceeded our design speed he saw that we had actually twisted the tailplane out of shape. Once we slowed down again it came back into shape, which was one of the advantages of a wooden aircraft. He didn’t tell me until after we landed. The reason we’d lost the German fighter was actually due to our last Tsetse pilot. Wally was an ex fighter man who was well practiced in fighter tactics, so when he saw the one on my tail being unfriendly, he broke off to attack. He found out later that his own violent turn threw off a fighter which was lining up to shoot him! His fire got the fighter off my tail. We lost a lot of aircraft. Over the VHF came the call from the deputy “reform out to sea” - everybody ignored it and headed for home, completely and utterly broke up.”

The Polish Mustangs had claimed four enemy fighters destroyed, plus another two FW190s which collided in mid air. The attacking force had lost a Mustang, a Beaufighter and the two Tsetse Mosquitoes from Beattie’s Flight. Beattie and Wally were told to go back to Sumburgh, which acted as an emergency landing station. Ten of the formation’s aircraft landed there.

Another Op was flown on the 9th to Ytteroene and Svino, 7000 feet overland.

On December 28th Beattie carried out a Rover from Karmoy to Ytvaer and attacked a motor vessel in Skudenshaven, which was reported in a national newspaper. “We fired twelve rounds in two attack runs. You could only get 6 or 7 in a single run.”

After completing his time with the SD Flight, Beattie moved on to No.1 Ferry Unit at Pershore, which was tasked with checking aircraft then taking them out to North Africa to then be taken on to the Far East for operations against the Japanese.

“In the 12 months I was at Pershore I did only two ferry trips; one to Cairo, the other to Algiers. For the rest of my time there the Station Adjutant grabbed me for all of the ‘P1’ work on the station: investigations, Courts of Enquiry, Summaries of Evidence leading to Courts Martial.”

With the end of the war the RAF, like every other service, was now given the enormous task of stepping down from a war footing and returning to normal peace time manning. With this, Beattie was given the opportunity to return to civilian life. He now lives in the North West of England but has maintained his Service links, and as a member of the RAFA has regular opportunities to visit RAF stations in the area. He still has several reminders of his career in Coastal Command; the metal punched out of his Hampden when he was hit by a flak ship, a deactivated 57mm shell from the Molins gun and a stuffed toy of a monkey in RAF uniform; a mascot which accompanied him on all but one of his operational sorties.

The author

Mark Barber, War Thunder Historical Consultant

Mark Barber, War Thunder Historical Consultant

Mark Barber is a pilot in the British Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm. His first book was published by Osprey Publishing in 2008; subsequently, he has written several more titles for Osprey and has also published articles for several magazines, including the UK's top selling aviation magazine 'FlyPast'. His main areas of interest are British Naval Aviation in the First and Second World Wars and RAF Fighter Command in the Second World War. He currently works with Gaijin Entertainment as a Historical Consultant, helping to run the Historical Section of the War Thunder forums and heading up the Ace of the Month series.