- For PC

- For MAC

- For Linux

- OS: Windows 10 (64 bit)

- Processor: Dual-Core 2.2 GHz

- Memory: 4GB

- Video Card: DirectX 11 level video card: AMD Radeon 77XX / NVIDIA GeForce GTX 660. The minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 23.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Windows 10/11 (64 bit)

- Processor: Intel Core i5 or Ryzen 5 3600 and better

- Memory: 16 GB and more

- Video Card: DirectX 11 level video card or higher and drivers: Nvidia GeForce 1060 and higher, Radeon RX 570 and higher

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 75.9 GB (Full client)

- OS: Mac OS Big Sur 11.0 or newer

- Processor: Core i5, minimum 2.2GHz (Intel Xeon is not supported)

- Memory: 6 GB

- Video Card: Intel Iris Pro 5200 (Mac), or analog from AMD/Nvidia for Mac. Minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p with Metal support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 22.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Mac OS Big Sur 11.0 or newer

- Processor: Core i7 (Intel Xeon is not supported)

- Memory: 8 GB

- Video Card: Radeon Vega II or higher with Metal support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 62.2 GB (Full client)

- OS: Most modern 64bit Linux distributions

- Processor: Dual-Core 2.4 GHz

- Memory: 4 GB

- Video Card: NVIDIA 660 with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) / similar AMD with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months; the minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p) with Vulkan support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 22.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Ubuntu 20.04 64bit

- Processor: Intel Core i7

- Memory: 16 GB

- Video Card: NVIDIA 1060 with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) / similar AMD (Radeon RX 570) with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) with Vulkan support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 62.2 GB (Full client)

by Mark Barber

It would be an understatement to say that RAF Fighter Command was poorly placed in terms of its tactics at the beginning of the Second World War. Britain had not been involved in a large conflict involving air-to-air combat since 1918, and many of the valuable lessons learned during the First World War had now been forgotten, erroneously dismissed as the tactics used in a bygone era and therefore no longer relevant.

Perhaps the most key strength of the fighter aircraft was its maneuverability; its freedom to move with speed and agility to engage an enemy aircraft. With war approaching in the 1930s, the hierarchy of Fighter Command now believed that this speed and agility was obsolete and that the key to breaking up mass formations of enemy bombers was rigid, regimented close formation flying. This has already been mentioned in a previous article, but let us examine it in a little more detail. Expecting war to come from Germany and proceeding under the belief that Germany did not possess any fighters with the range to fly to Britain, Fighter Command developed six ‘standard attacks’ for engaging large formations of enemy bombers:

Fighter Attack No.1 (From Above Cloud) {3 aircraft Section vs single enemy}

Fighter Attack No.2 (From Directly Below) {3 aircraft Section vs single enemy}

Fighter Attack No.3 (From Dead Astern) Approach Pursuit or Approach Turning

Fighter Attack No.4 (From Directly Below) {A variation of No.2, attacking multiple aircraft}

Fighter Attack No.5 (From Dead Astern) {For attacking a large enemy formation}

Fighter Attack No.6 (From Dead Astern) {Attack conducted with entire squadron}

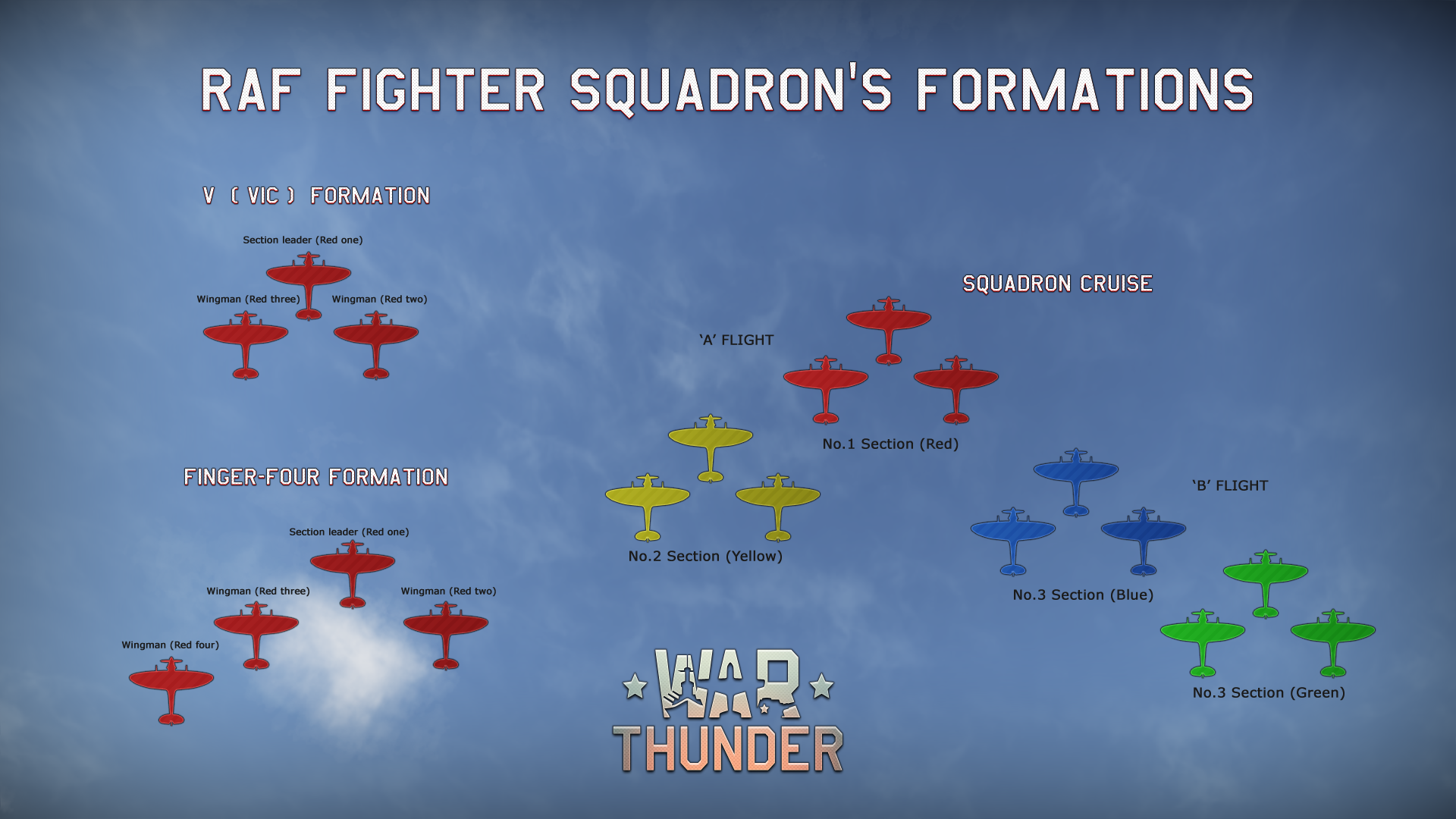

These attacks were so complex in execution that an entire chapter could be written on them; central to these standard attacks was formation flying. A Section of three fighters would fly in a tight ‘vic’ with the leader slightly ahead and his two wingmen who would be tucked in to either side with their wing tips only feet apart. Marshaled by a set of standardized vocal commands from their Section Leader, the vic would position to attack enemy bombers whilst maintaining formation at all times. Individual pilots would not fire their guns on their own initiative; they would wait for the command from their Section Leader, such as:

“Number One Section, fire… go.”

As dogfighting was believed to be a product of a bygone era, Fighter Command also believed that air-to-air gunnery was a tertiary skill. During the early months of the war it was not uncommon for a newly qualified fighter pilot to arrive at his squadron having never fired guns from an aircraft. Placing three fighters in tight formation with twenty four machine guns between them was considered more than adequate for filling the sky with bullets around the intended target – accuracy was not required. Furthermore the head of Fighter Command, Air Chief Marshall Sir Hugh Dowding, implemented a standard gun harmonization range for his fighters at 400 yards. The idea was to focus the fighter’s guns at a point which would leave the pilot shooting from a range long enough to keep him away from the bombers’ defensive fire.

In summary, at the beginning of the Second World War RAF Fighter Command’s standard operating procedures called for formation flying so rigid that only the Section Leader could look for enemy aircraft; his two wingmen were too concerned about collision avoidance. Fighter pilots’ gunnery was exceptionally poor, and this was compounded by gun harmonization set at too far a range to be effective. Pilots had lost the ability to dogfight and were trained to fly in a manner which completely negated the agility of their aircraft.

When RAF fighters were employed in France and Norway during 1940, the learning curve was steep. German tactics had been refined during the Spanish Civil War and it quickly became apparent that Fighter Command’s ‘Standard Tactics’ were useless. No.1 Squadron, operating Hurricanes in France, began to experiment with harmonizing their guns to a range of only 250 yards; news of their successes soon spread and individual squadrons began to replace the ‘Dowding Spread’ of 400 yards. By the time of the Battle of Britain in summer 1940 Fighter Command had learned, the hard way, that speed, flexibility and agility were the key to success and that airborne gunnery was a vital skill for a fighter pilot.

Taking yet more leads from the Luftwaffe, RAF Fighter Command also dispensed with the three aircraft ‘vic’ as its standard element. Luftwaffe fighters operated in ‘Schwarms’ of four aircraft which could then break down into ‘rotte’ of two aircraft; a leader to pursue the enemy and a wingman whose sole job was to protect his leader. Fighter Command implemented the ‘Finger Four’ – essentially a Schwarm – named after the positions of the four fighters in formation being similar to the fingertips of an outstretched hand.

Experienced fighter leaders were now realizing that pre-war doctrine was dangerously erroneous and set about establishing new procedures. One of the most famous examples of this was laid down by Squadron Leader Adolf ‘Sailor’ Malan, Commanding Officer of No.74 Squadron during the Battle of Britain. His ‘Ten of My Rules for Air to Air Fighting’ was so popular that it was published as a poster for all Fighter Command airfields:

“Wait until you see the whites of his eyes. Fire short bursts of 1 or 2 seconds and only when your sights are definitely ‘ON’.

Whilst shooting think of nothing else, brace the whole of the body, have both hands on the stick, concentrate on your ring sight.

Always keep a sharp lookout. ‘Keep your finger out’!

Height gives You the initiative.

Always turn and face the attack.

Make your decisions promptly. It is better to act quickly even though your tactics are not the best.

Never fly straight and level for more than 30 seconds in the combat area.

When diving to attack always leave a proportion of your formation above to act as top guard.

INITIATIVE, AGGRESSION, AIR DISCIPLINE and TEAM WORK are words that MEAN something in Air Fighting.

Go in quickly – Punch hard – Get out!”

Not only is it testament to Malan that some of these rules are still practiced today in the age of jet fighters, but it is also remarkable that many of these rules are similar if not identical to the rules of aerial combat laid down by the likes of Boelcke and Mannock during the First World War. Whilst there was certainly an element of uniformity binding the squadrons of Fighter Command together at the lower levels, debate raged about the actual employment of the squadrons themselves at the higher levels.

By 1941, RAF Fighter Command had made up for lost ground and was now fighting with tactics which no longer put them at a disadvantage during air-to-air combat. However, there were other problems to overcome.

After victory during the Battle of Britain, the policy decision was now made to take more of an offensive stance. Rather than defending home ground, Fighter Command would take to ‘Leaning into France’ – the new strategy now called for a show of dominance via offensive fighter sweeps over occupied Europe in an attempt to draw out the enemy. However, the simple adoption of tactics such as the ‘Finger Four’ were not enough to adapt to this new method of operating; fighters were now over enemy held territory without the benefit of radar or ground control giving them exact steers to engage an enemy force. Building on the ‘Big Wings’ utilized by 12 Group during the Battle of Britain, large numbers of fighters would escort small numbers of bombers on daylight raids. This met limited success’ the Luftwaffe would not be drawn out in force. Now that the Luftwaffe were on the defensive they possessed many of the advantages which had served the RAF during the summer of 1940, and with careful planning and organization, the RAF hunters often became the hunted. In the opening months of 1941, Fighter Command’s losses were greater than those of the Luftwaffe in Western Europe.

However, tactics had still advanced from the early days of the war and the flexibility afforded by the adoption of the Finger Four, closely harmonized guns and the ability to fly the aircraft to the edge of its performance envelope and shoot accurately would now see Fighter Command through to the end of the war.

Discuss the article and meet the aithor on the War Thunder official forums!

|

About the author:Mark Barber, War Thunder Historical ConsultantMark Barber is a pilot in the British Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm. His first book was published by Osprey Publishing in 2008; subsequently, he has written several more titles for Osprey and has also published articles for several magazines, including the UK's top selling aviation magazine 'FlyPast'. His main areas of interest are British Naval Aviation in the First and Second World Wars and RAF Fighter Command in the Second World War. He currently works with Gaijin as a Historical Consultant, helping to run the Historical Section of the War Thunder forums and heading up the Ace of the Month series. |