- For PC

- For MAC

- For Linux

- OS: Windows 10 (64 bit)

- Processor: Dual-Core 2.2 GHz

- Memory: 4GB

- Video Card: DirectX 11 level video card: AMD Radeon 77XX / NVIDIA GeForce GTX 660. The minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 23.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Windows 10/11 (64 bit)

- Processor: Intel Core i5 or Ryzen 5 3600 and better

- Memory: 16 GB and more

- Video Card: DirectX 11 level video card or higher and drivers: Nvidia GeForce 1060 and higher, Radeon RX 570 and higher

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 75.9 GB (Full client)

- OS: Mac OS Big Sur 11.0 or newer

- Processor: Core i5, minimum 2.2GHz (Intel Xeon is not supported)

- Memory: 6 GB

- Video Card: Intel Iris Pro 5200 (Mac), or analog from AMD/Nvidia for Mac. Minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p with Metal support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 22.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Mac OS Big Sur 11.0 or newer

- Processor: Core i7 (Intel Xeon is not supported)

- Memory: 8 GB

- Video Card: Radeon Vega II or higher with Metal support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 62.2 GB (Full client)

- OS: Most modern 64bit Linux distributions

- Processor: Dual-Core 2.4 GHz

- Memory: 4 GB

- Video Card: NVIDIA 660 with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) / similar AMD with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months; the minimum supported resolution for the game is 720p) with Vulkan support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 22.1 GB (Minimal client)

- OS: Ubuntu 20.04 64bit

- Processor: Intel Core i7

- Memory: 16 GB

- Video Card: NVIDIA 1060 with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) / similar AMD (Radeon RX 570) with latest proprietary drivers (not older than 6 months) with Vulkan support.

- Network: Broadband Internet connection

- Hard Drive: 62.2 GB (Full client)

Fighters such as the Spitfire, Bf 109 and A6M Zero have become immortal in the annals of aviation history. Bombers such as the B-17, Lancaster and Junkers Ju 88 are likewise remembered as pioneering designs and amongst the best of their role. But what the other designs? Aircraft which those with only a passing interest in aviation might never have even heard of, who carried out less glamourous but equally dangerous roles away from the spotlight occupied by more exciting and beautiful aircraft. War Thunder’s new ‘Ugly Duckling’ series will take a look at some of these aircraft, often cumbersome in appearance, limited in production run or carrying out roles little understood outside of aviation circles.

|

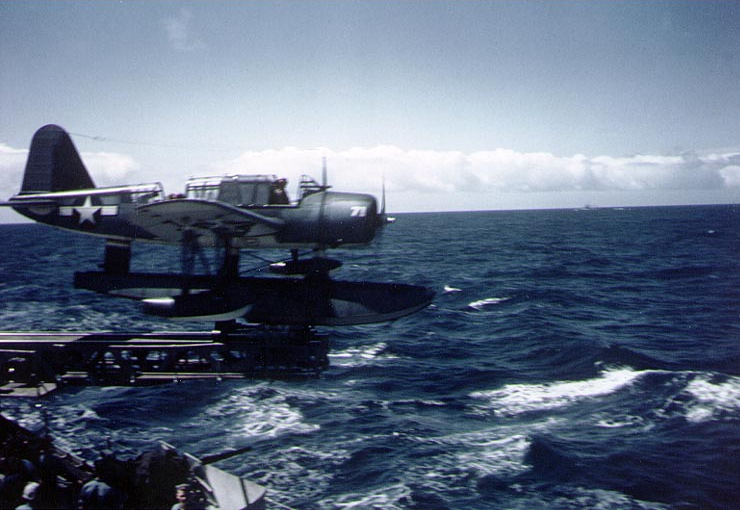

We will start with an aircraft which may not have possessed the glamour of the Corsair or the battle honours of the Dauntless. But, to hundreds of downed US Navy aircrew, countless merchant sailors who formed the lifelines of the allied war effort and thousands of US Marines who depended on accurate naval gunfire support as they pushed inland, this aircraft was even more of a welcome sight: the Kingfisher.

Designed as a replacement for the Vought O3U Corsair biplane, the OS2U Kingfisher was the US Navy’s first monoplane observation aircraft with the capability to be catapult launched from capital ships. It was also available as a more conventional landplane variant, with wheels replacing its floats. The type entered service in 1940, with the first aircraft being delivered to 32,600 ton battleship USS Colorado. Powered by a single 450 HP radial engine, the Kingfisher was capable of reaching speeds in excess of 160 mph and flying at heights up to 13,000 feet with a range of some 800 miles. Over the next two years, over 1500 Kingfishers were manufactured by Vought-Sikorsky in several different variants. So what was its actual job? The Kingfisher carried out many vital roles:

|

The eyes and ears of a fleet of warships are limited at best, particularly when seaborne radar is a rarity and, any vessels fortunate enough to be equipped with radar will be primitive at best in the early 1940s. This is where the observation aircraft is imperative. Even without the massive air support of a carrier, a battleship could catapult launch a Kingfisher seaplane. The aircraft could then patrol the surrounding seas for hundreds of miles for hours at a time. Depending on the threat, the Kingfisher might be looking for anything as huge as an enemy fleet or as small and deadly as a single enemy submarine. In the case of the latter, the Kingfisher had teeth of its own: even with its limited payload, Kingfishers assisted in the sinking of U-Boats U-576 and U-176.

Simply finding a target or enemy fleet was of immense use to the bridge crew of a warship, but the Kingfisher could do more. Once an enemy fleet was identified it was almost inevitable that an engagement would take place – even in the 1940s, naval guns were well capable of firing shells in excess of 20 miles. The Kingfisher, rocked and buffeted by AA fire from enemy ships, could fly over an enemy fleet and report directly back to the bridge crew of any warship within its own fleet, giving real time feedback of the accuracy of fall of shot and corrections to bring the tremendous firepower onto a target. Furthermore, the importance of naval gunfire did not stop with engaging other vessels: carrying some of the largest guns in the entire world on a mobile platform, battleships and their smaller brethren were the ultimate fire support during an amphibious assault. As US Marines fought their way from beachheads all across the Pacific theatre, the guns of the fleet were often there to eliminate concentrations of enemy troops and heavy defensive positions. Again, the Kingfisher was ideally placed to ensure this supporting fire was accurately and efficiently delivered.

|

To those it assisted, perhaps the role the Kingfisher is most affectionately remembered for is that of search and rescue. Even in peacetime, flying was and still is a hazardous occupation. During times of hostilities, before enemy action is even considered as a factor, accident rates in aviation increase considerably due to human error from increased pressure and the tendency to operate in more hostile environments and meteorological conditions for longer periods of time. It is often little appreciated just how many aircraft are lost during wartime due to weather, mechanical error or human error, and this is before a single shot has been fired by the enemy.

Whatever the reason, be it in terrible weather where nobody else will fly or in the face of the enemy against aircraft with a huge performance advantage, the Kingfisher was representative of the elite cadre of aircrew who risked all to try to save their comrades who had already fallen. One famous example of this occurred in November 1942; World War One flying ace Eddie Rickenbacker and his crew had survived the ditching of a B-17 in the Pacific and had been adrift for days in their life rafts. A Kingfisher eventually found the crew and managed to rescue five of the eight man crew. The next day the Kingfisher returned to rescue Rickenbacker and the other two remaining crewmen. Given the conditions and the loads involved, the Kingfisher did not possess the performance margin to take off and so water taxied 40 miles to the nearest point of land. In April 1944 the crew of a Kingfisher were able to transport 10 downed US airmen from Truk Lagoon to the submarine USS Tang.

|

The Kingfisher also saw widespread export success, with 100 being operated by the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm, as well as orders to Australia, the Netherlands, Mexico, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay and the Dominican Republic.

In War Thunder, the Kingfisher can currently only be used in a very minor role compared to its importance some seventy years ago. It is easy to dismiss the aircraft; it stood no chance against a Bf 109 or A6M Zero. But, this was not its role. A Bf 109 could not launch from a light cruiser, patrol a convoy route for several hours, attack submarines with depth charges, correct naval gunfire support to troops advancing across islands in the Pacific or rescue downed airmen. Next time you click past the Kingfisher on your menu screen, spare a thought for the bravery of the airmen who risked everything in the worst weather imaginable to help their fallen comrades, or braved the fire of the enemy without a squadron of sleek, modern eight gun fighters to even the odds.

About The Author

|

Mark Barber, War Thunder Historical Consultant Mark Barber is a pilot in the British Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm. His first book was published by Osprey Publishing in 2008; subsequently, he has written several more titles for Osprey and has also published articles for several magazines, including the UK's top selling aviation magazine 'FlyPast'. His main areas of interest are British Naval Aviation in the First and Second World Wars and RAF Fighter Command in the Second World War. He currently works with Gaijin Entertainment as a Historical Consultant, helping to run the Historical Section of the War Thunder forums and heading up the Ace of the Month series. |